When we left off with Part 1, Harry Anslinger had used a mad propaganda campaign to paint cannabis as a dangerous scourge that came from Black communities. He’d succeeded in getting the states to sign on to matching cannabis legislation, and had succeeded in passing the Marijuana Tax Act, essentially outlawing recreational cannabis.

But he wasn’t done.

Jazz and Propaganda

Making marijuana illegal on the federal level hadn’t reduced Harry Anslinger’s zeal for putting Black and brown people in their place.

"There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers,” he said. “Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others."

Cannabis was still popular among musicians, and that couldn’t be allowed under Anslinger’s watch. Over the next few years, 3,000 to 4,000 cannabis sellers per year, plus countless users, were arrested. One of Anslinger’s agents admitted that they targeted musicians because they were common reefer smokers.

But not just any musicians. “Arrests involving a certain type of musician in marihuana cases are on the increase,” Anslinger wrote. “I am not talking about the good musicians, but the Jazz type.” The Black type.

He was particularly obsessed with Billie Holiday and the famous song Strange Fruit. Her performances of the anti-lynching song caught Anslinger’s attention. He ordered her to stop performing it, and she refused. Unfortunately, she also had an addiction, which gave Anslinger considerable power over her.

Holliday was harassed, arrested and stripped of her cabaret license. Later, she was arrested again on flimsy evidence — a stash of opium in an adjacent room and a shooting kit which was conveniently misplaced. She was arrested for possession for the last time while she was dying of cirrhosis of the liver. They handcuffed her to her hospital bed.

John C. McWilliams, author of The Protectors: Harry J. Anslinger and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, 1930-1962, said, “Anslinger’s wasn’t so much a war on drugs as it was a war on culture, an attempt to squelch the radical freedom of the Jazz Age for people of color. Anslinger was a xenophobe with no capacity for intellectual nuance, and his racist views informed his work to devastating effect.”

Gateway Drugs and Mandatory Minimums

After the heady years of World War II, there was an increase in narcotic drug use in the U.S. Anslinger claimed he could stem this with harsher penalties for drug users, starting with cannabis.

After all, he claimed, cannabis was a “gateway drug,” which led to the use of harder drugs like heroin down the line. Interestingly, during the 1937 hearings on the Marijuana Tax Act, Anslinger sang a different tune.

He was asked “whether the marijuana addict graduates into a heroin, an opium, or a cocaine user?” Anslinger replied, “No, sir. I have not heard of a case of that kind. I think it is an entirely different class. The marijuana addict does not go in that direction.”

But in the early 1950s, he told Congress, “The danger is this: Over 50% of these young addicts started on marihuana smoking. They started there and graduated to heroin; they took the needle when the thrill of marihuana was gone.”

The Narcotics Control Act of 1956 quietly integrated cannabis into narcotics legislation and set the precedent of legislating cannabis just like heroin. The new law set new mandatory minimum sentences of two to five years for first time cannabis offenses.

The 1960s

It’s at this point that we say goodbye to Mr. Anslinger, who retired in the early 1960s.

For a fun bit of revisionist history, I suggest you check out the DEA Museum website’s history of Mr. Anslinger’s life. He’s presented as a reluctant administrator who “[brought] marijuana under federal control,” making him a “lightning rod for today’s critics of the federal government’s role in regulating marijuana.” The Marijuana Tax Act is never mentioned, nor are his numerous recorded statements of racism and xenophobia.

Cannabis use — and arrests — continued to increase through the 1960s. In 1960, there were just 5,155 arrests in California for cannabis. By 1967, there were over 37,000 arrests. Over half were white.

Although the hysteria surrounding cannabis had mostly passed, the legal side effects had not. A Saturday Evening Post article from 1966 states, “By general medical agreement, marijuana is not addictive. It almost never leaves a hangover. It is less damaging, physically, than alcohol. Some psychiatrists and doctors believe that the drug should be legalized, and eventually will be. They predict that marijuana will someday rival liquor as the prime social intoxicant.”

The 1960s also saw the end of the Marijuana Tax Act. Famous psychologist and psychedelic advocate Timothy Leary was arrested and convicted for possession of marijuana under the 1937 law, but he successfully appealed. The Tax Act required that he confess to the possession of the drugs in order to pay the required taxes — but that meant self-incriminating, which violated his Fifth Amendment rights.

Unfortunately, the Act was quickly replaced with the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act in 1970, which temporarily classified cannabis as a Schedule 1 substance. This classification claims that it has “no currently accepted medical use” and has high potential for addiction. This is the framework that federal law still operates under today.

The Nixon Years

The Nixon Years

Nixon entered office in 1969 with his own drug agenda aimed in two very specific directions. Close advisor John Ehrlichman later admitted, “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people...We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities.”

To support this aim, Nixon intended for cannabis to stay right where it was — as a Schedule 1 Substance according to the Controlled Substances Act. He tasked the the Shafer Commission with producing a study that would provide a recommendation for permanently classifying cannabis as a Schedule 1 narcotic.

The resulting report, Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding was a shock to Nixon. It said that cannabis wasn’t addictive or harmful, debunked the gateway drug theory, and proposed that prohibition should be ended.

Nixon was not pleased. He sent pro-segregation Senator James Eastland to hold hearings, bringing in “experts” who instead toed the party line — that cannabis was dangerous, caused street crime, and could result in brain damage.

Cannabis remained a Schedule 1 narcotic, and it is this designation which has prevented the study of medical marijuana over the past 50 years.

Just Say No (to Racism)

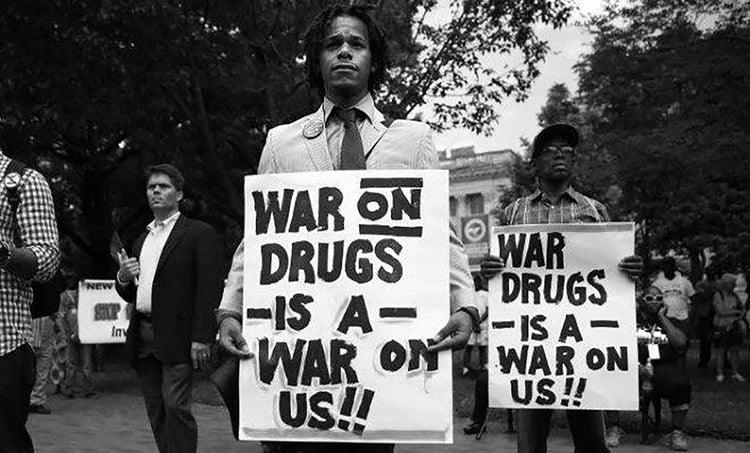

While cannabis was well-entrenched as an illegal substance by the time of the Reagan administration, it wasn’t until the 1980s that arrests of Black men and other people of color for drug possession really exploded.

Between 1980 and 2000, the number of people in American prisons and jails jumped from 300,000 to more than 2 million — mostly due to drug arrests. And 80% of those drug arrests were due to marijuana.

Reagan’s War on Drugs gave police unprecedented latitude to stop and search nearly anyone they wished, for any pretext — a traffic violation, a driving checkpoint, jaywalking, a bulge in the pocket. This method was taught in 1984’s Operation Pipeline, a DEA program that trains local law enforcement in using traffic stops and “consensual searches” on a massive scale, looking for drugs.

To incentivize police further to fight this war, Congress made millions of dollars of federal grant money available to local law enforcement that uses the funds for fighting drug crimes. The result has been a major increase in narcotics task forces.

And the targets of these task forces have been primarily Black and Latino, due in large part to the Reagan administration's media campaign that pushed the image of the poor Black crack addict. While no one would come out and say “Black people are drug addicts,” the imagery was clear and prolific.

In a 1995 survey published by the Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, respondents were asked, “Would you close your eyes for a second, envision a drug user, and describe that person to me?”

95% of survey takers described a Black drug user. That year, only 15% of drug users were in fact Black. These biases affect not only civilians. They affect law enforcement, lawyers, judges, and policy makers. If everyone involved in the process of making and enforcing drug law thinks that Black people are more likely to be offenders, the result is a drastic inequality in the way drug laws are made and enforced.

And we’re seeing it in action. By 2000, prison admissions for Black people were more than 26 times higher than the levels of 1983.

Lest we make the mistake of blaming only Republicans for an overly aggressive drug policy, remember that every president since Reagan has fallen over himself to appear tough on crime.

Clinton, for example, escalated the drug war and implemented a federal “three strikes” law. The number of incarcerees on both the state and federal level rose faster under Clinton than any other president.

AIDS and Medical Marijuana

The slow reversal of the government’s vice-like grip on medical marijuana is the result of AIDS-related activism.

With the Reagan administration doing nothing to respond to the crisis, AIDS patients and their loved ones would travel to Mexico and other countries to bring home experimental medications in an attempt to find a cure, or at least allay the symptoms.

Many also turned to marijuana to help stimulate their appetites. Patients reported that cannabis helped ease the gastrointestinal distress caused by both the illness and AZT, a medication that slowed viral replication.

Activists began to push for access to medical marijuana for AIDS patients and others. Nearly 80% of voters in San Francisco voted to approve the use of medical marijuana in 1991. The movement spread, and by 1996, California had formally legalized medical marijuana.

Since then, nearly every state has passed some form of medical marijuana policy — although many are still highly restricted and only allow for low-THC cannabis. But with recreational cannabis legal in 11 states, it’s only a matter of time before prohibition is a thing of the past.

Racist Legacy

While things are moving in the right direction, there’s a legacy of racism and discrimination lying in the wake of cannabis prohibition.

Black people and people of color are 8 times more likely to be arrested for violating cannabis law. Non-users are harassed and searched on flimsy pretexts. Arrests, even without a conviction, can result in lost jobs, wages, inability to find work, and high fines that can cripple the poor.

Most illegal drug users and dealers are white. And yet, three-quarters of all people imprisoned for drug offenses have been Black or Latino.

The legacy of Anslinger and his racist, self-serving cannabis hysteria has long shadows. Cannabis legalization is on the horizon. But it will be many more decades before we can undo the damage that a century of fear-mongering and xenophobia has wrought.

For more information on this subject, try:

• Cannabis: the Illegalization of Weed in America by Box Brown

• The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander

• Cannabis: A History by Martin Booth

• The Emperor Wears No Clothes By Jack Herer